“A Royal Visit” post by Alessandra Tanesini on Changing Attitudes in Public Discourse

In Brazil, social-media-induced polarization and apathy may linger long after the last vote has been counted.

The Washington Post article:

“No court would convict Trump of incitement. His liability is moral, not legal.” by

Addressing a culture of disrespect: Arrogance and Anger in Debate.

by Alessandra Tanesini

Public debates throughout the Western World have descended into polarized shouting matches. Mocking, bullying and silencing one’s opponents have become omnipresent in the context of discussions where winning is everything and the truth counts for nought. While there might be circumstances where anger and forceful indignation are warranted, there is little doubt that the current climate is one in which disrespect for one’s political opponents is prevalent.

Our times are characterized by widespread uninhibited anger. But ours is also an age of arrogance. It is arrogance that is responsible for the mocking, the bullying, and the silencing. When President Trump mocks Christine Blasey Ford who had not targeted him in her dignified testimony to the US Senate Judiciary Committee, arrogance is on display.

There is a special kind of arrogance that I have labelled haughtiness or superbia that manifests itself in a need to do others down so that one can feel superior to them. It is the form of arrogance of those who are obsessed with winning, who are prone to humiliate others in many ways and to refer to them as losers.

I have argued elsewhere arrogance is often associated with anger.[1] Anger is a negative response directed at a person who is perceived as having done intentionally something that wronged us or those we hold near and dear. The desire to retaliate is also an intimate element of anger. Some of the wrongs that elicit anger in response are slights or personal insults. These are perceived wrongs that directly harm the social status of the person who has been harmed in this way.

Arrogant individuals experience mere disagreements or requests for clarifications as slights and affronts. Although this perception is often unwarranted, arrogant people behave in this way because, often unconsciously, they think of themselves as judges or referees. They behave as if their opinions had the force of verdicts rather than of contributions made by equal discussants in debates. That is, these arrogant individuals feel that their views are not up for discussion. It is this sense of entitlement that causes them to experience challenges as affronts. It is also the basis of their feelings of superiority.

Since arrogant people experience disagreement as a slight -a threat to social status- they respond by trying to get even. Hence, they are angry. They take themselves to be entitled to a place at the top of the pecking order. It is a pecking order that they are keen to defend by mocking, humiliating, angrily intimidating other people.

Because the arrogant person ties up in his mind his own self-esteem and self-respect with being superior to others and with deserving special entitlements, his sense of self-worth is fragile. Ordinary behaviour by other people is felt as a threat to the self. The perceived slight instigates a desire to do others down to preserve one’s special entitlements. This is why arrogant people are angry.

Arrogance and anger feed each other. They are part of a vicious circle of ever increasing aggression and disrespect. The arrogant person needs to feel superior in order to have a good opinion of himself. He experiences equal treatment as an insult that must be remedied. Experiencing disagreement as a slight threatens to lower the social status of the arrogant individual at least in his own eyes. He feels he risks becoming the kind of person that others think can be treated like anyone else. Since he feels diminished, he reacts in anger to restore his self-esteem. But this anger, this need for retaliation, exacerbates the fragility of his self-esteem. He thus becomes more defensive, more arrogant and then even more disposed to anger.

These considerations suggest the hypothesis that arrogance is a defensive mechanism adopted by those whose high self-opinion is insecure. They hide their insecurity through aggression. There is empirical support for this proposition. Social psychologists have found that some individuals possess attitudes to the self that are discrepant. These people appear to have a high opinion of themselves as these attitudes are measured explicitly by means of questionnaires. However, when their attitudes about themselves are measured indirectly they appear to have low self-esteem. Indirect measures include Implicit Association Tests but also assessments of the name letter effect where the extent to which subjects prefer the first letter of their proper names is measured. Those people who have high self-esteem in explicit measures and low implicitly measured self-esteem are described as possessing defensive high self-esteem. These are individuals who are very defensive, act arrogantly, are boastful, are on average more prejudiced than other people, and are disposed to anger. In sum, there is reason to believe that arrogance is underpinned by defensive high self-esteem.[2]

In our current work for the project Changing Attitudes in Public Discourse we are testing whether defensive high self-esteem is predictive of seemingly arrogant behaviours in debate. These include being disposed to interrupt other speakers without possessing a similar tendency to offer supportive feedback. We are also developing an intervention to reduce arrogance in debate. We are testing whether self-affirmation techniques, designed to make the self less vulnerable to threats, might be effective in promoting humbler and calmer behaviour in debate. The preliminary results of this study will be available early next year on our website.

[1] Tanesini, A. Forthcoming. ‘Arrogance, Anger and Debate’, Symposion: Theoretical and Applied Inquiries in Philosophy and Social Sciences, Special issue on Skeptical Problems in Political Epistemology, edited by Scott Aikin and Tempest Henning. For a draft visit, https://tanesini.wordpress.com/publications/.

[2] For more details on the empirical literature, see Tanesini, A. In Press. ‘Reducing Arrogance in Public Debate’, In J. Arthur (Ed.), Virtues in the Public Sphere (pp. 28-38). London: Routledge. For a draft see https://tanesini.wordpress.com/publications/

With Michael Lynch

The word has taken a beating in the past few weeks. But what role does it truly play in our lives?

By Paul Bloomfield

Mr. Bloomfield is a professor of philosophy at the University of Connecticut.

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Deliberating with Humility on Human Rights Issues

By Sandra Sirota

Postdoctoral Researcher

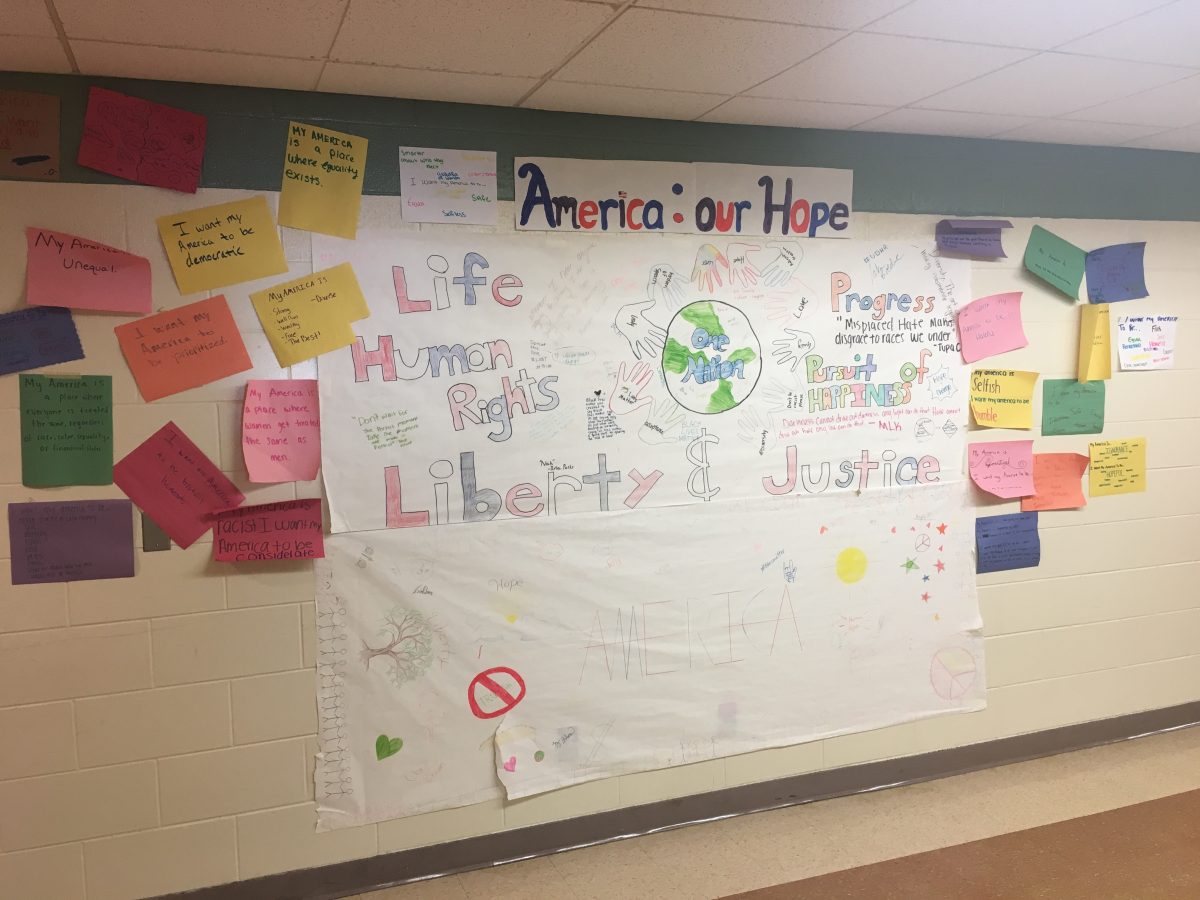

This past spring, I introduced the Human Rights Education and Deliberation program in Manchester High School as part of the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project. With support from trained facilitators who are University of Connecticut junior and senior undergraduates majoring in human rights, I taught human rights and deliberation skills to the students.

By human rights, I mean education about, through, and for human rights, which is elaborated on in the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training as

With a central aim of human rights education being to ensure all people are treated with respect, one way to do this is to listen to others with an open mind. Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse share that intellectual humility (IH) “involves being able to embrace one’s beliefs with confidence while being open to alternative evidence” (2016, p. 210). They define it as “a nonthreatening awareness of one’s intellectual fallibility” (2016, p. 210). In measuring IH, they seek to provide a reliable measure which can then be used in developing an understanding if IH can contribute to more peaceful interactions within society and socio-politically at both the micro and macro level (Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse, 2010).

This idea of contributing to a more peaceful society relates to the goals of human rights education in ensuring all humans are treated with dignity and respect. By combining human rights education and deliberation skills-building in a high school classroom setting, I seek to understand whether students develop the knowledge and skills to deliberate on controversial issues with humility and open-mindedness. In exploring this connection, I draw on Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse’s study which states that “the IH scale would predict key outcomes of IH, specifically open-mindedness and tolerance, above the tendency to desire understanding and engage in critical thinking.” (p. 211).

Building on this idea, my research question is: How does participation in a human rights education and deliberation skills program influence students’ ability to engage in deliberations on controversial issues with open-mindedness and intellectual humility? Relatedly, I seek to understand whether students change their views about their own intellectual humility.

The Human Rights Education and Deliberation Program

In three human rights classes, over ten sessions, students practiced deliberating on controversial human rights issues. Each class chose a topic to research and then deliberate on in order to come up with a plan to protect human rights. One class chose to deliberate on whether they think the crisis in Syria constitutes a genocide, and what action should be taken to stop human rights violations there. A second class focused on creating a plan to protect Dreamers – undocumented people living in the United States who were brought to this country as children. The third class deliberated on how to end police brutality in the United States. The goal for the students was to share their ideas respectfully and learn from each other in order to decide collaboratively on the best way to protect human rights related to their chosen topic.

I examined whether this process of deliberating on controversial human rights issues supported the students in developing skills to deliberate with humility and open-mindedness. Could, and would, the students apply this skill even when they held strong convictions on the topic on which they were deliberating? Participation in a human rights class often has the aims of instilling knowledge, values, and skills to promote human rights (Bajaj, 2011; Flowers, 2003; Hantzopoulos, 2012; Kingston, 2014; Tibbitts, 2002). In order to advocate for human rights, it is certainly helpful to have a strong conviction that one’s beliefs are morally correct. It would be quite difficult to advocate effectively for an end to police brutality without a steadfast position against it. At the same time, a central value to be upheld in human rights education classes is that all people should be treated with respect and dignity (Bajaj, 2011; Flowers, 2003; Hantzopoulos, 2012; Kingston, 2014; Tibbitts, 2002), including individuals with opposing points of view.

The Human Rights Education and Deliberation program wrapped up in June. I, with Research Assistant, Rasa Davidaviciute, administered the pre- and post-program survey created by Mancuso and Rouse (see “The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale”), conducted pre- and post-program individual interviews and focus groups, and observed class sessions. We administered the survey and conducted individual interviews and focus groups with two classes at the high school who served as a control group as well. The control group classes did not receive the 10-session human rights education and deliberation skills-building class.

What happens when people in the same community, family, workplace, or classroom disagree on human rights and related issues such as politics and religion? This question informs the larger goal of my research – to explore the connection between human rights education and gaining the skills to deliberate with intellectual humility and open-mindedness. Having just completed the project in the high school, we are in the process of analyzing data and will share the results of this research soon.

References / Literature Review:

Bajaj, M. (2011). Human rights education: Ideology, location, and approaches. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(2), 481-508.

Flowers, N. (2003). What is human rights education. A survey of human rights education, 107-118.

Hantzopoulos, M. (2012). Considering human rights education as US public school reform. Peace Review, 24(1), 36-45.

Kingston, L. N. (2014). The rise of human rights education: Opportunities, challenges, and future possibilities. Societies Without Borders, 9(2), 188-210.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive intellectual humility scale. Journal of personality assessment, 98(2), 209-221.

Tibbitts, F. (2002). Understanding what we do: Emerging models for human rights education. International Review of Education, 48(3-4), 159-171.

UNOHCHR (2011). United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training. Retrieved January 12, 2017 from http://daccess-ddsny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/ N11/467/04/PDF/N1146704.pdf? OpenElement.