Lauren Swayne Barthold is a residential research fellow with the Humanities Institute’s Humility and Conviction in Public Life Project

Lauren Swayne Barthold is a residential research fellow with the Humanities Institute’s Humility and Conviction in Public Life Project

H&C: What is your academic background and what is your current position in UCHI/at UConn/Your Home Institution?

LB: For the past 11 years I have taught in the philosophy department at Gordon College, where I helped start and then direct the Gender Studies Minor. My main areas of teaching have been ethics, gender studies, pragmatism, and feminist theology. My scholarship has primarily focused on the the twentieth-century German philosopher, Hans-Georg Gadamer, who was instrumental in developing what’s called “philosophical hermeneutics.” Hermeneutics refers to the “art of interpretation” and although it originally applied to texts, today philosophical hermeneutics explores what it means to understand in general. What goes on in the process of understanding? Much of my writing has been devoted to demonstrating the relevance of philosophical hermeneutics for other areas of thought. For instance, my most recent book, A Hermeneutic Approach to Gender and Other Social Identities, uses hermeneutics to develop a theory of social identities. I have also written on a hermeneutic approach to the ethics of bio-enhancement.

H&C: What is the project you’re currently working on?

LB: I am working on a new book project called Critical, Fallible Dialogue, which fits really well with the “Humility and Conviction” theme. A good dialogue is one that starts from a place of strong conviction, where something is at stake. Because something is at stake one is motivated to critically reflect on the issue, one’s own position, and the merits of the other’s position. Dialogue is not an empty exchange in which anything goes. At the same time, we need to acknowledge our own fallibility. We don’t know everything–even if (especially if!) we have strong convictions about something. When we engage with another it’s important to come with the humility that one’s own position is fallible. How do we balance critique with fallibilism? What other factors contribute to a strong dialogue? What sorts of structural practices curtail or foster a good dialogue? My new book attempts to answer these questions by developing an interdisciplinary model of dialogue drawing on Buber, Gadamer, feminist theorists, critics of deliberative democracy, and dialogic practitioners.

H&C: How did you arrive at this topic?

LB: Gadamer, in part, drew on the work of Martin Buber’s seminal I and Thou to demonstrate the dialogical nature of understanding and some of my previous work has articulated a concept of dialogue based on Gadamer’s hermeneutics. But also, personally, having spent most of my life in fairly conservative religious environments, I’ve seen the importance of trying to figure out how people with strong convictions can get along with those who hold different convictions. How do we address difference? How do we get along with others who disagree with us? Obviously there is no shortage of conviction in most religious communities! How do we create spaces for critique and critical reflection within and among religious communities is a question I’ve struggled with for most of my life. Personally, I reject all forms of violence (and threats of violence) as a solution. And since I would name (some forms of) silence and silencing others as a form of violence—choosing not to talk to others is not a viable option. So how do we talk with others who hold very different sets of convictions? What does philosophy have to say about this? In general, philosophers have tended to focus on what I call a hyper-rationalistic model that privileges an exchange of reasons. This is exemplified by two of the most important political philosophers of the twentieth century, Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls. Both devoted their lives’ works to figuring out how citizens can cultivate strong and peaceful democracies based on an exchange of reasons. And while I think the work they have done is tremendously important, my sense is that it takes seriously only one dimension of the human, that is, reason. If we are not just “rational animals” but also relational and emotional animals, then what does a successful model of discourse look like? When people come together, when we talk about creating community, persuading one another, agreement, and living together, focusing on reason alone is not necessarily the best way to create strong democratic and peaceful communities. When one looks at the work that dialogic practitioners do, one sees not only the limitations of focusing on reason alone but how doing so can actually heighten conflict. The “Power of Dialogue” training I received with Essential Partners (Cambridge, MA) was an excellent way for me to experience first hand a more experiential approach to dialogue. My book is an attempt to bring all these parts of my life and research together.

H&C: What impact might your work have on a larger public understanding of your topic?

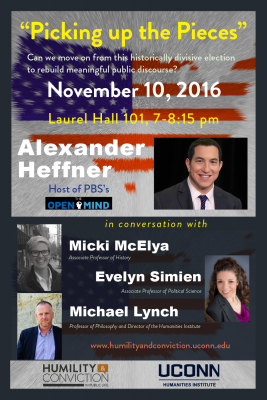

LB: Unfortunately in the US, there is not much of an appreciation for public intellectuals. I am thrilled that part of Michael Lynch’s vision for the Humanities Institute is to work to change that by inviting academics to conceive a wider audience for their work. Humanists need a venue to get excited about the wider relevance of their work! While by the end of the twentieth century American philosophers had cloistered themselves off from the public, that had not always been case for philosophers. American pragmatism at the beginning of the twentieth century provides excellent examples, like John Dewey, of powerful philosophic voices that spoke to current issues. And I had the good fortune of studying with the contemporary pragmatist Richard Bernstein who, following in the footsteps of John Dewey, modeled an “engaged, fallibilistic pluralism” not only in his academic scholarship but in his role as a teacher and as a human being. My aim in writing my present book is to encourage people to take seriously the roll of dialogue in a democracy. I hope that as we come together to try to reinvigorate our democracy at this critical juncture, we will consider anew what it means to be active democratic citizens, and realize that dialogue is fundamental to that project.

Amy Shuster (Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy The Ohio State University)

Amy Shuster (Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy The Ohio State University)