The Humility and Conviction in Public Life Project at the University of Connecticut announces its 2018 Summer Institute for Early College Experience (ECE) Teachers:

Teaching Conviction, Humility, and “the Facts” in the American Studies Classroom

In a time of “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and cries from across the political spectrum that truth is dead, the American Studies classroom is more heated, energizing, and necessary than ever. This UConn Summer Institute on Teaching Conviction, Humility, and “the Facts” will provide an opportunity for teachers of American Studies in the Early College Experience Program to come together for the week of July 23-27 to learn methods for navigating this environment and guiding your students in productive and intellectually diverse dialogues about American culture, history, and politics. While working with leading scholars of intellectual humility, truth & public life, and American Studies, this institute is an opportunity for collaboration and community building among ECE teacher-scholars from around the state. In addition to pedagogy work, topics for consideration and possible lesson adoption may include: the press, visual culture, and the Spanish American War; national apologies & reparations for slavery, Indian Boarding Schools & Japanese American Internment; Fascism and Populism in America over time; WWII, Vietnam & the Fog of War; and the Legacies of Watergate.

Morning sessions will be lecture and discussion. Afternoon sessions will be small-group collaboration with a focus on pedagogical techniques and curriculum development in consultation with institute leaders and visiting specialists. Participants will finish the week with new classroom methods, lesson plans, and syllabi.

Confirmed speakers include:

Heather Battaly, Professor of Philosophy, UConn

Michael P. Lynch, Director of the UConn Humanities Institute, Principal Investigator for the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project, and Professor of Philosophy, UConn

Micki McElya, Professor of History, UConn, and Director of the 2018 HCPL Summer Institute

Bonnie Miller, Associate Professor of American Studies, UMass Boston

Sandra Sirota, Postdoctoral Researcher with the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project, and Co-Coordinator of the 2018 HCPL Summer Institute

Chris Vials, Director of the American Studies Program, and Associate Professor of English, UConn

For more information, contact: sandra.sirota@uconn.edu

If you require an accommodation to participate, please contact Humanities Institute staff

(Nasya Al-Saidy) at uchi@uconn.edu or phone (860) 486-9057 by July 18, 2018

Deliberating with Humility on Human Rights Issues

By Sandra Sirota

Postdoctoral Researcher

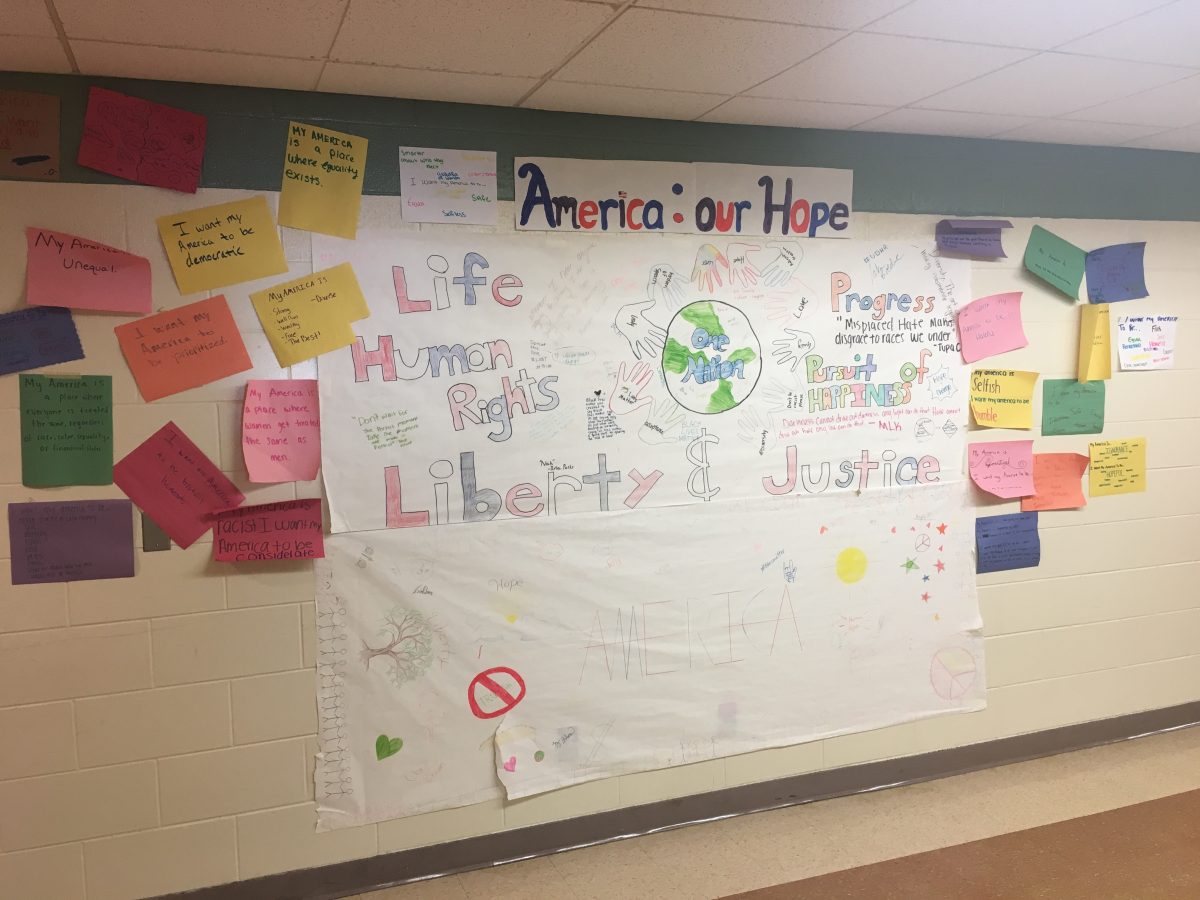

This past spring, I introduced the Human Rights Education and Deliberation program in Manchester High School as part of the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project. With support from trained facilitators who are University of Connecticut junior and senior undergraduates majoring in human rights, I taught human rights and deliberation skills to the students.

By human rights, I mean education about, through, and for human rights, which is elaborated on in the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training as

With a central aim of human rights education being to ensure all people are treated with respect, one way to do this is to listen to others with an open mind. Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse share that intellectual humility (IH) “involves being able to embrace one’s beliefs with confidence while being open to alternative evidence” (2016, p. 210). They define it as “a nonthreatening awareness of one’s intellectual fallibility” (2016, p. 210). In measuring IH, they seek to provide a reliable measure which can then be used in developing an understanding if IH can contribute to more peaceful interactions within society and socio-politically at both the micro and macro level (Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse, 2010).

This idea of contributing to a more peaceful society relates to the goals of human rights education in ensuring all humans are treated with dignity and respect. By combining human rights education and deliberation skills-building in a high school classroom setting, I seek to understand whether students develop the knowledge and skills to deliberate on controversial issues with humility and open-mindedness. In exploring this connection, I draw on Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse’s study which states that “the IH scale would predict key outcomes of IH, specifically open-mindedness and tolerance, above the tendency to desire understanding and engage in critical thinking.” (p. 211).

Building on this idea, my research question is: How does participation in a human rights education and deliberation skills program influence students’ ability to engage in deliberations on controversial issues with open-mindedness and intellectual humility? Relatedly, I seek to understand whether students change their views about their own intellectual humility.

The Human Rights Education and Deliberation Program

In three human rights classes, over ten sessions, students practiced deliberating on controversial human rights issues. Each class chose a topic to research and then deliberate on in order to come up with a plan to protect human rights. One class chose to deliberate on whether they think the crisis in Syria constitutes a genocide, and what action should be taken to stop human rights violations there. A second class focused on creating a plan to protect Dreamers – undocumented people living in the United States who were brought to this country as children. The third class deliberated on how to end police brutality in the United States. The goal for the students was to share their ideas respectfully and learn from each other in order to decide collaboratively on the best way to protect human rights related to their chosen topic.

I examined whether this process of deliberating on controversial human rights issues supported the students in developing skills to deliberate with humility and open-mindedness. Could, and would, the students apply this skill even when they held strong convictions on the topic on which they were deliberating? Participation in a human rights class often has the aims of instilling knowledge, values, and skills to promote human rights (Bajaj, 2011; Flowers, 2003; Hantzopoulos, 2012; Kingston, 2014; Tibbitts, 2002). In order to advocate for human rights, it is certainly helpful to have a strong conviction that one’s beliefs are morally correct. It would be quite difficult to advocate effectively for an end to police brutality without a steadfast position against it. At the same time, a central value to be upheld in human rights education classes is that all people should be treated with respect and dignity (Bajaj, 2011; Flowers, 2003; Hantzopoulos, 2012; Kingston, 2014; Tibbitts, 2002), including individuals with opposing points of view.

The Human Rights Education and Deliberation program wrapped up in June. I, with Research Assistant, Rasa Davidaviciute, administered the pre- and post-program survey created by Mancuso and Rouse (see “The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale”), conducted pre- and post-program individual interviews and focus groups, and observed class sessions. We administered the survey and conducted individual interviews and focus groups with two classes at the high school who served as a control group as well. The control group classes did not receive the 10-session human rights education and deliberation skills-building class.

What happens when people in the same community, family, workplace, or classroom disagree on human rights and related issues such as politics and religion? This question informs the larger goal of my research – to explore the connection between human rights education and gaining the skills to deliberate with intellectual humility and open-mindedness. Having just completed the project in the high school, we are in the process of analyzing data and will share the results of this research soon.

References / Literature Review:

Bajaj, M. (2011). Human rights education: Ideology, location, and approaches. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(2), 481-508.

Flowers, N. (2003). What is human rights education. A survey of human rights education, 107-118.

Hantzopoulos, M. (2012). Considering human rights education as US public school reform. Peace Review, 24(1), 36-45.

Kingston, L. N. (2014). The rise of human rights education: Opportunities, challenges, and future possibilities. Societies Without Borders, 9(2), 188-210.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive intellectual humility scale. Journal of personality assessment, 98(2), 209-221.

Tibbitts, F. (2002). Understanding what we do: Emerging models for human rights education. International Review of Education, 48(3-4), 159-171.

UNOHCHR (2011). United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training. Retrieved January 12, 2017 from http://daccess-ddsny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/ N11/467/04/PDF/N1146704.pdf? OpenElement.