Why Ask Questions?

By Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Scott Brummel,

Joshua August Skorburg, and Jordan Carpenter (Duke University)

Political polarization is rampant in the United States and around the world. This epidemic undermines community and social progress. Members of different political parties misunderstand, hate, and avoid each other. Our government does little to solve pressing problems.

This complaint is common, but what can we do about it? Love is all you need, the Beatles sang. That answer is too simple, but at least we should not hate everyone who disagrees with us. The real question, however, is what practical steps can we personally take to turn hatred into love or at least respect? People need to escape their echo chambers to encounter new perspectives, but how can we convince them to leave their friends for a while and listen to their enemies? The government needs to escape gridlock, but what can we do to make Congress act? It is easy to complain and hard to solve such large problems.

Although individuals cannot change the government or prevent trolling on the internet, we can improve our own beliefs and actions, and we can affect a few of the few people we meet. That achievement is limited but worthwhile. We can benefit from talking to neighbors with different views, even if we cannot talk to political leaders. We should not give up on reducing polarization in our own lives just because we cannot end it everywhere.

What can we do on a personal level to end polarization? First, we can stop abusing others by calling them crazy, stupid, ignorant, selfish, or ridiculous. Those labels are rarely accurate and hinder our own thinking as well as communication with others. Second, we can stop isolating ourselves and instead seek out people with conflicting political positions and listen charitably to them. It is usually not worth wasting time on rigid extremists on either side, but many moderates are willing to listen and learn as well as teach.

But how can we start a conversation with political opponents? One strategy is to assert your position and let them assert theirs. Bare assertions rarely work with adversaries, however. It is better for each side to give reasons why they hold their positions, but even reasoned arguments can turn people off when injected too early.

A better strategy to get communication going was illustrated by a television discussion many years ago (before YouTube!) between a biologist and a creation scientist. Many biologists disdain creation scientists, and they deserve it, but showing disdain will not fertilize fruitful exchange. If a biologist acts like a know-it-all, creation scientists will counter with their own claims and authorities, so then the discussion goes nowhere. This biologist was smarter than that. She simply asked questions: What do you believe? Are these beliefs based on scientific evidence? Which experiments have you done? How did you control for these confounds? How does that process work? Were your results replicated? Were they published? Which kind of journal? How did opponents respond? What more research is going on now? These questions were asked in a tone of voice that suggested curiosity instead of contempt. As a result, the biologist never came across as aggressive while many problems for creationism became obvious to the audience. The creationist was not convinced, of course, but careful listeners could not have missed the point.

This incident convinced me of the power of questions. If we want to understand and communicate with opponents, especially on controversial issues, it is usually more effective to ask questions than to assert truths.

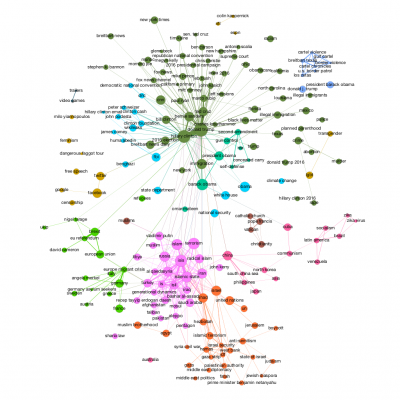

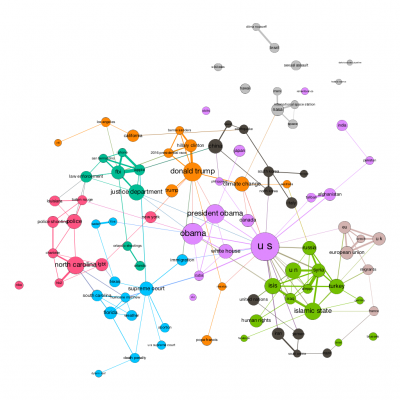

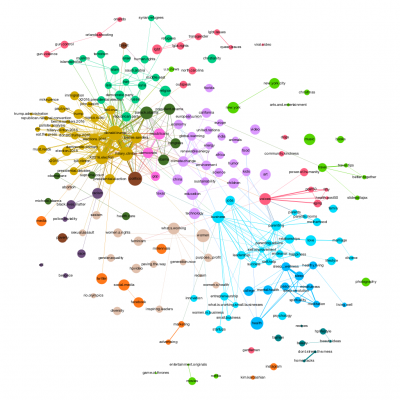

Admittedly, not every question succeeds. How can we tell which questions produce desired outcomes? Our current project tries to tackle that issue empirically. In our first stage, we asked online participants which questions they would pose if they wanted to win a conversation or refute an opponent (such as “Do you realize how stupid you are?” or “Don’t you care about innocent children?”). We asked other participants which questions they would ask if their goal was to understand an issue or to be respected and liked by an interlocutor (“What do you think we can agree about?”).

In a second stage, we asked a separate sample of participants to identify which of the goals listed above was intended by provided questions from our first stage. One initial lesson from this research is that questions intended to make people like the questioner (such as “Where did you grow up?”) usually do not increase understanding of the opposing argument, whereas questions that are seen as seeking information (such as “Could you please explain your position to me so that I can make sure that I understand it properly?”) do seem to lead to increased understanding. Another lesson is that people who are asked questions often misconstrue the intentions of the person who asks the question. Our future research will try to figure out which kinds of questions are misconstrued and why, so that we can make positive recommendations about which questions lead to mutual understanding and fruitful dialogue.

INSERT FIGURE HERE OR IN OR NEXT TO THE PRECEDING PARAGRAPH.

We hope eventually to build our findings into a training program for middle and high school students. The goal is to help students build good habits of questioning in the right ways at the right times in order to increase respect and to reduce polarization. Successful programs will depend on strong empirical evidence, so we will need to continue our research. In the meantime, we can all learn to assert less and ask more, and we can try our best to introduce the right questions into the right contexts. These skills can enable us to start constructive conversations with political opponents, so we can each personally do our little bit to start to solve some small part of the big problem of polarization that is tearing our society apart.

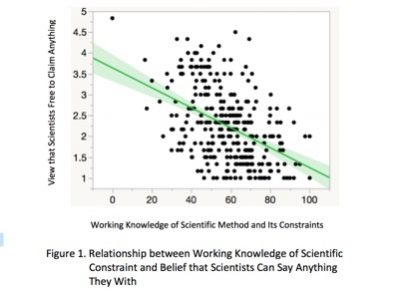

Measures of self-rated improved understanding of the issues among people who answered questions emerging from each of the four manipulated motivations. Participants felt like they learned little about the issue from answering questions intended to engender across-the-aisle liking and respect.

Measures of self-rated improved understanding of the issues among people who answered questions emerging from each of the four manipulated motivations. Participants felt like they learned little about the issue from answering questions intended to engender across-the-aisle liking and respect.

Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization

Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization