The Humility and Conviction in Public Life Project at the University of Connecticut announces its 2018 Summer Institute for Early College Experience (ECE) Teachers:

Teaching Conviction, Humility, and “the Facts” in the American Studies Classroom

In a time of “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and cries from across the political spectrum that truth is dead, the American Studies classroom is more heated, energizing, and necessary than ever. This UConn Summer Institute on Teaching Conviction, Humility, and “the Facts” will provide an opportunity for teachers of American Studies in the Early College Experience Program to come together for the week of July 23-27 to learn methods for navigating this environment and guiding your students in productive and intellectually diverse dialogues about American culture, history, and politics. While working with leading scholars of intellectual humility, truth & public life, and American Studies, this institute is an opportunity for collaboration and community building among ECE teacher-scholars from around the state. In addition to pedagogy work, topics for consideration and possible lesson adoption may include: the press, visual culture, and the Spanish American War; national apologies & reparations for slavery, Indian Boarding Schools & Japanese American Internment; Fascism and Populism in America over time; WWII, Vietnam & the Fog of War; and the Legacies of Watergate.

Morning sessions will be lecture and discussion. Afternoon sessions will be small-group collaboration with a focus on pedagogical techniques and curriculum development in consultation with institute leaders and visiting specialists. Participants will finish the week with new classroom methods, lesson plans, and syllabi.

Confirmed speakers include:

Heather Battaly, Professor of Philosophy, UConn

Michael P. Lynch, Director of the UConn Humanities Institute, Principal Investigator for the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project, and Professor of Philosophy, UConn

Micki McElya, Professor of History, UConn, and Director of the 2018 HCPL Summer Institute

Bonnie Miller, Associate Professor of American Studies, UMass Boston

Sandra Sirota, Postdoctoral Researcher with the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project, and Co-Coordinator of the 2018 HCPL Summer Institute

Chris Vials, Director of the American Studies Program, and Associate Professor of English, UConn

For more information, contact: sandra.sirota@uconn.edu

If you require an accommodation to participate, please contact Humanities Institute staff

(Nasya Al-Saidy) at uchi@uconn.edu or phone (860) 486-9057 by July 18, 2018

Deliberating with Humility on Human Rights Issues

By Sandra Sirota

Postdoctoral Researcher

This past spring, I introduced the Human Rights Education and Deliberation program in Manchester High School as part of the Humility and Conviction in Public Life project. With support from trained facilitators who are University of Connecticut junior and senior undergraduates majoring in human rights, I taught human rights and deliberation skills to the students.

By human rights, I mean education about, through, and for human rights, which is elaborated on in the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training as

With a central aim of human rights education being to ensure all people are treated with respect, one way to do this is to listen to others with an open mind. Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse share that intellectual humility (IH) “involves being able to embrace one’s beliefs with confidence while being open to alternative evidence” (2016, p. 210). They define it as “a nonthreatening awareness of one’s intellectual fallibility” (2016, p. 210). In measuring IH, they seek to provide a reliable measure which can then be used in developing an understanding if IH can contribute to more peaceful interactions within society and socio-politically at both the micro and macro level (Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse, 2010).

This idea of contributing to a more peaceful society relates to the goals of human rights education in ensuring all humans are treated with dignity and respect. By combining human rights education and deliberation skills-building in a high school classroom setting, I seek to understand whether students develop the knowledge and skills to deliberate on controversial issues with humility and open-mindedness. In exploring this connection, I draw on Krumrei-Mancuso and Rouse’s study which states that “the IH scale would predict key outcomes of IH, specifically open-mindedness and tolerance, above the tendency to desire understanding and engage in critical thinking.” (p. 211).

Building on this idea, my research question is: How does participation in a human rights education and deliberation skills program influence students’ ability to engage in deliberations on controversial issues with open-mindedness and intellectual humility? Relatedly, I seek to understand whether students change their views about their own intellectual humility.

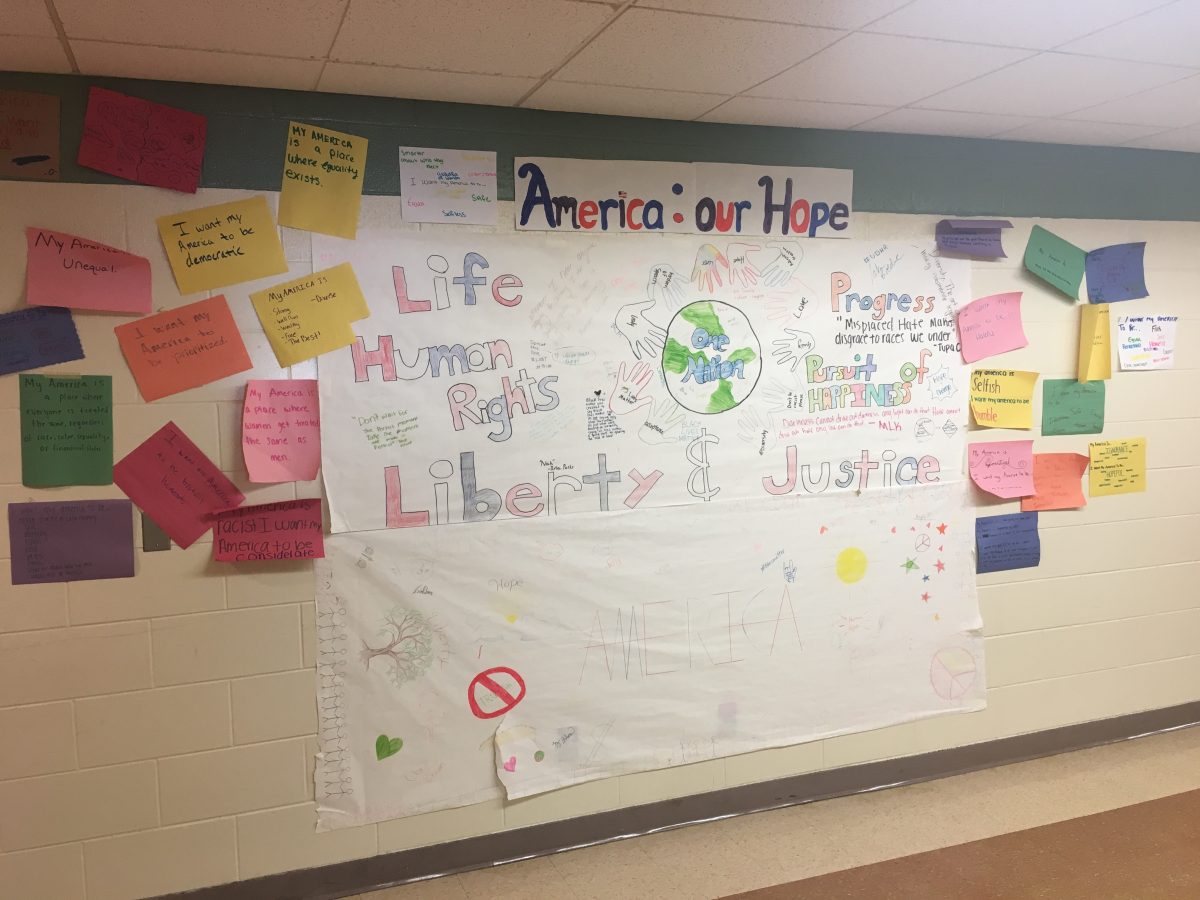

The Human Rights Education and Deliberation Program

In three human rights classes, over ten sessions, students practiced deliberating on controversial human rights issues. Each class chose a topic to research and then deliberate on in order to come up with a plan to protect human rights. One class chose to deliberate on whether they think the crisis in Syria constitutes a genocide, and what action should be taken to stop human rights violations there. A second class focused on creating a plan to protect Dreamers – undocumented people living in the United States who were brought to this country as children. The third class deliberated on how to end police brutality in the United States. The goal for the students was to share their ideas respectfully and learn from each other in order to decide collaboratively on the best way to protect human rights related to their chosen topic.

I examined whether this process of deliberating on controversial human rights issues supported the students in developing skills to deliberate with humility and open-mindedness. Could, and would, the students apply this skill even when they held strong convictions on the topic on which they were deliberating? Participation in a human rights class often has the aims of instilling knowledge, values, and skills to promote human rights (Bajaj, 2011; Flowers, 2003; Hantzopoulos, 2012; Kingston, 2014; Tibbitts, 2002). In order to advocate for human rights, it is certainly helpful to have a strong conviction that one’s beliefs are morally correct. It would be quite difficult to advocate effectively for an end to police brutality without a steadfast position against it. At the same time, a central value to be upheld in human rights education classes is that all people should be treated with respect and dignity (Bajaj, 2011; Flowers, 2003; Hantzopoulos, 2012; Kingston, 2014; Tibbitts, 2002), including individuals with opposing points of view.

The Human Rights Education and Deliberation program wrapped up in June. I, with Research Assistant, Rasa Davidaviciute, administered the pre- and post-program survey created by Mancuso and Rouse (see “The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale”), conducted pre- and post-program individual interviews and focus groups, and observed class sessions. We administered the survey and conducted individual interviews and focus groups with two classes at the high school who served as a control group as well. The control group classes did not receive the 10-session human rights education and deliberation skills-building class.

What happens when people in the same community, family, workplace, or classroom disagree on human rights and related issues such as politics and religion? This question informs the larger goal of my research – to explore the connection between human rights education and gaining the skills to deliberate with intellectual humility and open-mindedness. Having just completed the project in the high school, we are in the process of analyzing data and will share the results of this research soon.

References / Literature Review:

Bajaj, M. (2011). Human rights education: Ideology, location, and approaches. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(2), 481-508.

Flowers, N. (2003). What is human rights education. A survey of human rights education, 107-118.

Hantzopoulos, M. (2012). Considering human rights education as US public school reform. Peace Review, 24(1), 36-45.

Kingston, L. N. (2014). The rise of human rights education: Opportunities, challenges, and future possibilities. Societies Without Borders, 9(2), 188-210.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive intellectual humility scale. Journal of personality assessment, 98(2), 209-221.

Tibbitts, F. (2002). Understanding what we do: Emerging models for human rights education. International Review of Education, 48(3-4), 159-171.

UNOHCHR (2011). United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training. Retrieved January 12, 2017 from http://daccess-ddsny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/ N11/467/04/PDF/N1146704.pdf? OpenElement.

Why Ask Questions?

By Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Scott Brummel,

Joshua August Skorburg, and Jordan Carpenter (Duke University)

Political polarization is rampant in the United States and around the world. This epidemic undermines community and social progress. Members of different political parties misunderstand, hate, and avoid each other. Our government does little to solve pressing problems.

This complaint is common, but what can we do about it? Love is all you need, the Beatles sang. That answer is too simple, but at least we should not hate everyone who disagrees with us. The real question, however, is what practical steps can we personally take to turn hatred into love or at least respect? People need to escape their echo chambers to encounter new perspectives, but how can we convince them to leave their friends for a while and listen to their enemies? The government needs to escape gridlock, but what can we do to make Congress act? It is easy to complain and hard to solve such large problems.

Although individuals cannot change the government or prevent trolling on the internet, we can improve our own beliefs and actions, and we can affect a few of the few people we meet. That achievement is limited but worthwhile. We can benefit from talking to neighbors with different views, even if we cannot talk to political leaders. We should not give up on reducing polarization in our own lives just because we cannot end it everywhere.

What can we do on a personal level to end polarization? First, we can stop abusing others by calling them crazy, stupid, ignorant, selfish, or ridiculous. Those labels are rarely accurate and hinder our own thinking as well as communication with others. Second, we can stop isolating ourselves and instead seek out people with conflicting political positions and listen charitably to them. It is usually not worth wasting time on rigid extremists on either side, but many moderates are willing to listen and learn as well as teach.

But how can we start a conversation with political opponents? One strategy is to assert your position and let them assert theirs. Bare assertions rarely work with adversaries, however. It is better for each side to give reasons why they hold their positions, but even reasoned arguments can turn people off when injected too early.

A better strategy to get communication going was illustrated by a television discussion many years ago (before YouTube!) between a biologist and a creation scientist. Many biologists disdain creation scientists, and they deserve it, but showing disdain will not fertilize fruitful exchange. If a biologist acts like a know-it-all, creation scientists will counter with their own claims and authorities, so then the discussion goes nowhere. This biologist was smarter than that. She simply asked questions: What do you believe? Are these beliefs based on scientific evidence? Which experiments have you done? How did you control for these confounds? How does that process work? Were your results replicated? Were they published? Which kind of journal? How did opponents respond? What more research is going on now? These questions were asked in a tone of voice that suggested curiosity instead of contempt. As a result, the biologist never came across as aggressive while many problems for creationism became obvious to the audience. The creationist was not convinced, of course, but careful listeners could not have missed the point.

This incident convinced me of the power of questions. If we want to understand and communicate with opponents, especially on controversial issues, it is usually more effective to ask questions than to assert truths.

Admittedly, not every question succeeds. How can we tell which questions produce desired outcomes? Our current project tries to tackle that issue empirically. In our first stage, we asked online participants which questions they would pose if they wanted to win a conversation or refute an opponent (such as “Do you realize how stupid you are?” or “Don’t you care about innocent children?”). We asked other participants which questions they would ask if their goal was to understand an issue or to be respected and liked by an interlocutor (“What do you think we can agree about?”).

In a second stage, we asked a separate sample of participants to identify which of the goals listed above was intended by provided questions from our first stage. One initial lesson from this research is that questions intended to make people like the questioner (such as “Where did you grow up?”) usually do not increase understanding of the opposing argument, whereas questions that are seen as seeking information (such as “Could you please explain your position to me so that I can make sure that I understand it properly?”) do seem to lead to increased understanding. Another lesson is that people who are asked questions often misconstrue the intentions of the person who asks the question. Our future research will try to figure out which kinds of questions are misconstrued and why, so that we can make positive recommendations about which questions lead to mutual understanding and fruitful dialogue.

INSERT FIGURE HERE OR IN OR NEXT TO THE PRECEDING PARAGRAPH.

We hope eventually to build our findings into a training program for middle and high school students. The goal is to help students build good habits of questioning in the right ways at the right times in order to increase respect and to reduce polarization. Successful programs will depend on strong empirical evidence, so we will need to continue our research. In the meantime, we can all learn to assert less and ask more, and we can try our best to introduce the right questions into the right contexts. These skills can enable us to start constructive conversations with political opponents, so we can each personally do our little bit to start to solve some small part of the big problem of polarization that is tearing our society apart.

Measures of self-rated improved understanding of the issues among people who answered questions emerging from each of the four manipulated motivations. Participants felt like they learned little about the issue from answering questions intended to engender across-the-aisle liking and respect.

Measures of self-rated improved understanding of the issues among people who answered questions emerging from each of the four manipulated motivations. Participants felt like they learned little about the issue from answering questions intended to engender across-the-aisle liking and respect.

On April 25, 2018, Humility and Conviction in Public Life and CTForum hosted its Midpoint Forum “Talking About Faith and Politics: Navigating our difference with humility and conviction,” at the Wadsworth Atheneum museum in Hartford. With an introduction by Philosopher, Project co-PI, and director of the UConn Humanities Institute Michael Lynch, and moderated by John Dankosky, the editor of the New England News Collaborative, the lively conversation included some of the nation’s leading thinkers about the intersection of religion and politics. The panel, political commentator and former presidential advisor David Gergen, educator and founding director of Resetting the Table, Rabbi Melissa Weintraub, and founding director of the Interfaith Youth Core, Eboo Patel, discussed a wide range of topics from intellectual and religious diversity on college campuses and humility amongst our political leaders, to the type of religious diversity intended by the founding fathers.