Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization

Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization

by Mark Alfano

The 2015 Charleston church mass shooting, which left 9 dead, was planned and executed by Dylann Roof, an unrepentant white supremacist. According to prosecutors, Roof was found not to have adopted his convictions ‘through his personal associations or experiences with white supremacist groups or individuals or others,’ but instead to have developed them through his own efforts online. The same is true of Jose Pimentel, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Omar Mateen, and others.

The specific mechanisms by which the Internet facilitates self-radicalization are disputed. One popular view is that the Internet generates an echo-chamber effect: people interested in radical ideology tend to communicate directly or indirectly only with each other, reinforcing their predilections.

Surrounding the relatively rare problem of lone-wolf terrorism lies the much more common problem of self-radicalization that results in less dramatic but still worrisome actions and attitudes. The “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017 brought together neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and white nationalistic sympathizers for one of the largest in-person hate-themed meetings in the United States in decades. Many of the participants in this rally were organized and recruited via the Internet. Even more broadly, white supremacists and their sympathizers met and organized on r/The_Donald (a Reddit community), 4chan, and other online spaces during the 2016 American presidential campaign that resulted in the election of Donald Trump.

In my work on public discourse, I’ve developed a theory of online radicalization that I call the seduction model. According to John Forrester (1990, p. 42), “the first step in a seductive maneuver could be summed up as, ‘I know what you’re thinking.’” This gambit expresses several underlying attitudes. First, it evinces “the assumption of authority that seduction requires.” The authority in question is epistemic rather than the authority of force. Seduction is distinguished from assault by the fact that it aims at, requires, even fetishizes consent. The seducer insists that he is better-placed to know what the seducee thinks than the seducee himself is. Second, ‘I know what you’re thinking’ presupposes or establishes an intimate bond. Third, ‘I know what you’re thinking’ blurs the line between assertion, imperative, and declaration. This is because human agency and cognition are often scaffolded on dialogical processes. We find out what we think by expressing it and hearing it echoed back in a way we can accept, and by having thoughts attributed to us and agreeing with those.

The seduction model encompasses two ways in which information technologies play the functional role of the seducer by telling users of the Internet, “I know what you’re thinking.” What I call top-down technological seduction is imposed by technological designers, who, in structuring technological architecture, invite users to accept that their own thinking is similarly structured. In so doing, designers encourage or ‘nudge’ the user towards certain prescribed kinds of choices and attitudes. Top-down technological seduction needn’t be a matter of saying or implying, “I know that you’re thinking that p.” It can instead be structural. When Netizens are invited to accept that their own thinking is structured in socially dangerous or hateful ways — as opposed to overly simplistic and misguided ways, choice architects can seduce users to embrace prejudiced and hateful attitudes.

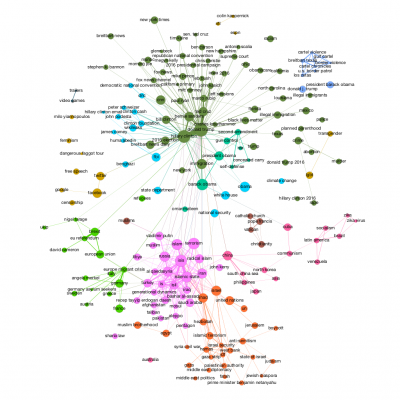

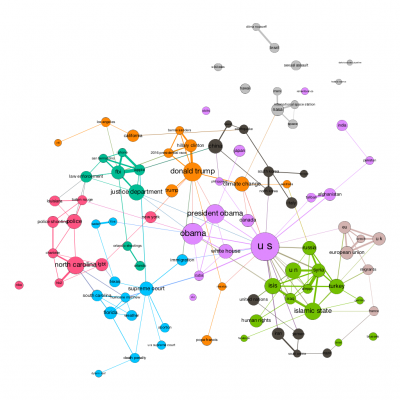

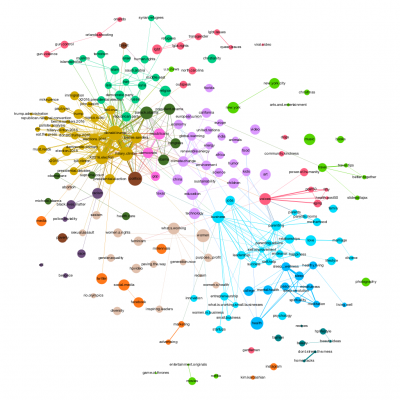

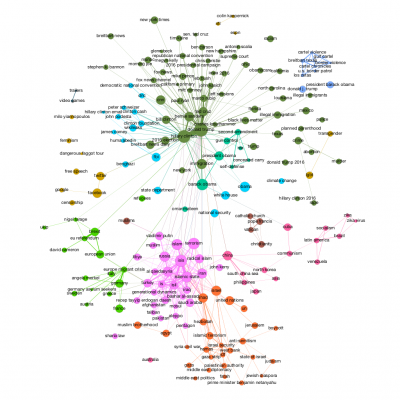

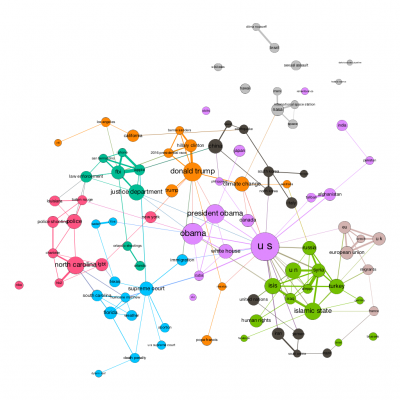

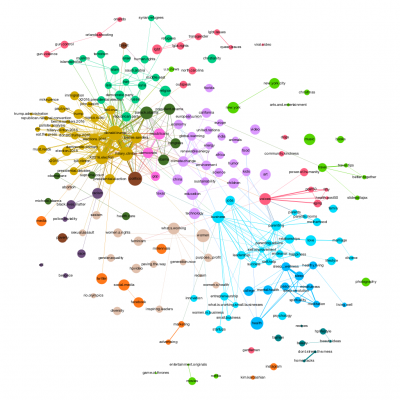

Using a digital humanities methodology, I compare the semantic tags on all stories published in 2016 by Breitbart with the tags used by other news organizations. It quickly becomes clear that the world will look very different to a Breitbart reader than it does to an NPR reader or a Huffington Post reader (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1. Network of the top 200 semantic tags on Breitbart in 2016. Layout = ForceAtlas. Node size = PageRank. Node color = semantic community membership. Edge width = frequency of co-occurrence.

Figure 2. Network of the top 100 semantic tags on NPR’s “The Two Way” news section in 2016. Layout = ForceAtlas. Node size = PageRank. Node color = semantic community membership. Edge width = frequency of co-occurrence. Only 100 semantic tags were chosen for NPR due to its overall sample size which is one order of magnitude less than Huffington Post and Breitbart.

Figure 3. Network of the top 200 semantic tags on the Huffington Post in 2016. Layout = ForceAtlas. Node size = PageRank. Node color = semantic community membership. Edge width = frequency of co-occurrence.

Breitbart consumers see in a world in which the most important news is that Mexican cartels commit atrocities in Texas, Muslim terrorist immigrants rampage through Europe, Barack Obama conspires with the United Nations and Jews, Russia and Turkey intervene in Syria to help fight the Islamic State, Donald Trump prepares to put a stop to illegal immigration to the United States, and Milo Yiannopoulos campaigns against Islam with his “Dangerous Faggot Tour.” Readers of other sites encounter a host of other phenomena that fit less easily into Breitbart’s Manichean worldview, such as right-wing attacks against the LGBT community, Dylann Roof’s sentencing, law enforcement agencies wrestling with technology companies over consumer privacy, and NASA’s exploration of the solar system.

Whereas top-down technological seduction plays out through the agency of designers, bottom-up technological seduction can occur without the involvement of anyone’s agency other than the seducee. It creates suggestions based either on aggregating other users’ information or by personalizing for each user based on their location, search history, and other data. It takes a user’s own record of engagement as the basis for saying, “I know what you’re thinking.” Bottom-up seduction can say, “I know what you’re thinking” because it can justifiably say, “I know what you and people like you thought, and what those other people went on to think.” It occurs when profiling enables both predictive and prescriptive analytics to bypass a user’s capacity for reasoning. I understand reasoning as the iterative, potentially path-dependent, process of asking and answering of questions. Profiling enables online interfaces to tailor both search suggestions (using predictive analytics) and answers to search queries (using prescriptive analytics) to an individual user.

Consider a simple and familiar example: predictive analytics will suggest, based on a user’s profile and the initial text string they enter, which query they might want to run. For instance, if you type ‘why are women’ into Google’s search bar, you are likely to see suggested queries such as ‘why are women colder than men’, ‘why are women protesting’, and ‘why are women so mean’. And if you type ‘why are men’ into Google’s search bar, you are likely to see suggested queries such as ‘why are men jerks’, ‘why are men taller than women’, and ‘why are men attracted to breasts’. These are cases of predictive analytics, which not only predicts but also suggests queries to users based on profiling, with or without aggregation.

Prescriptive analytics in turn suggests answers based on both the query someone actually runs and their online profile. In response to ‘why are women colder than men’, Google suggests a post titled “Why are Women Always Cold and Men Always Hot,” which claims that differences between the sexes in the phenomenology of temperature are due to the fact that men have scrotums. In response to ‘why are men jerks’, Google suggests a post titled “The Truth Behind Why Men are Assholes,” which contends that men need to act like assholes to establish their dominance and ensure a balance of power between the sexes.

Google suggests questions and then answers to those very questions, thereby closing the loop on the first stage of an iterative, path-dependent process of reasoning. If reasoning is the process of asking and answering questions, then the interaction between predictive and prescriptive analytics can largely bypass the individual’s contribution to reasoning, supplying both the question and the answer to it. When such predictive and prescriptive analytics are based in part on the user’s profile, Google is in effect saying, “I know what you’re thinking because I know what you and those like you thought.”

References

Forrester, John. (1990). The Seductions of Psychoanalysis: Freud, Lacan, and Derrida. Cambridge University Press.

Sanford Goldberg

Sanford Goldberg

Trystan Goetze

Trystan Goetze

Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization

Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization